GENERAL BENJAMIN BUTLER'S

Louisiana

Native Guard

|

General Butler initially resisted the enlistment of Black troops into the Union Army. In early August, Brigadier General John W Phelps requested permission from Butler to start a black regiment. Butler refused, stating that only Lincoln had the authority to start black regiments under the 2nd Confiscation Act of July17, 1862. Phelps was ordered to use the Negroes as laborers. Phelps was angered by the order and resigned.

Perhaps it was a case of brutality that he had to rule on. A young lady was brought to his attention at his headquarters. The girl was beautiful and probably reminded him of one of his own children. Her back was scared and disfigured by the repeated tear of the bullwhip. The perpetrator was her father and her master. Reports of the incident suggested that Butler was deeply shaken, stunned and never the same again.

“RESPECTABLE MERCHANT” AND HIS SLAVE DAUGHTER.

"One Sunday morning, while General Butler was seated at the breakfast table, Major Strong, a gentleman who was not given to undue emotion, rushed into the room, pale with rage and horror.

"General," he exclaimed, "there is the most list damnable thing out here!”… The woman who was the object of so much attention, was nearly white, aged about twenty-seven…"Look here, General," said Major Strong, as he opened the dress of this poor creature.

Her back was cut to pieces with the infernal cowhide. It was all black and red-red where and the infernal instrument of torture had broken the skin, black where it had not. To convey an idea of its appearance, General Strong used to yon say that it resembled a very rare beefsteak, with Ire the black marks of the gridiron across it.

No one ever saw General Butler so profoundly for moved as he was while gazing upon this pitiable ten spectacle. Who did this?" he asked the girl.

"Master," she replied.

"Who is your master?"

"Mr. Landry”

Landry was a respectable merchant living in near by quarters, not unknown to the members of the staff.

"What did he do it for?" asked the general.

"I went out after the clothes from the wash," said she, "and I stayed out late. When I then came home, master licked me and said he would teach me to run away."…At this moment Major Strong whispered in the general's ear a piece of information which I caused him to compare the faces of the master and the slave. The resemblance between them was striking.

"Is this woman your daughter?" asked the met general.

"There are reports to that effect," said Landry. … The general, for once, seemed deprived of his power to judge with promptness. He remained for some time," says an eye-witness, "apparently lost in abstraction. I shall never forget the singular expression on his face.

"I bad been accustomed to see him in a storm of passion at any instance of oppression or flagrant injustice; but on this occasion he was too deeply affected to obtain relief in the usual way.

"His whole air was one of dejection, almost listlessness; his indignation too intense, and his anger too stern, to find expression even in his countenance.

"Never have I seen that peculiar look but on three or four occasions similar to the one I am narrating when I knew he was pondering upon the baleful curse that had cast its withering blight upon all around, until the manhood and humanity were crushed out of the people, and outrages such as the above were looked upon with complacency, and the perpetrators treated as respected and worthy citizens,-and that he was realizing the great truth, that, however man might endeavor to guide this war to the advantage of a favorite idea or sagacious policy, the Almighty was directing it surely and steadily for the purification of our country from this greatest of national sins…I close this chapter of horrors. Each of these anecdotes illustrates one phase of the accursed thing, and all of them tend to show what has been already remarked, that the worst consequences of slavery fall upon the white race. It is better to be murdered than to be a murderer. It is better to be the victim of cruelty than to be capable of inflicting it. Mrs. Kemble judges rightly, when she says, in her recent noble and well-timed work, that it were far preferable to be a slave upon a Georgian rice plantation than to be the lord of one, with all that weight of crime upon the soul which slavery necessitates, and to become so completely depraved as to be able to contemplate so much suffering and iniquity with stolid indifference…But a woman's bleeding back, the master's brutal insensibility, the absolute destruction in the character of slave-owners of all that redeems human nature, such as sense of truth, pity the helpless, regard for the sanctities of domestic life; the flighty inferiority of their minds, their stupid improvidence, their incurable wrong-headedness and wrong-heartedness, their childish vanity and shameful ignorance, their boastful at emptiness and contempt for all people and nations more enlightened than themselves; these things appealed to him, these things he marked and inwardly digested. Impatient as he had previously been at the slow progress of the war, he now became more reconciled to it, because he saw that every month of its continuance made the doom of slavery more certain and more speedy. He was now perfectly aware that the United States could never realize General of Washington's modest aspiration, that it might become "a respectable nation," much less a great and glorious one, nor even a nation homogeneous enough to be truly powerful, until slavery had ceased to exist in every part of it.

Those who lived on intimate relations with the general, remarked his growing abhorrence of It slavery. During the first weeks of the occupation of the city, he was occasionally capable, in the hurry of indorsing a peck of letters, of spelling negro with two g's. Not so in the later months. Not so when he had seen the torn and bleeding and blackened backs of fair and delicate in women. Not so when he had reviewed his noble colored regiments. Not so when he had learned that the negroes of the South were among the heaven-destined means of restoring the integrity, the power, and the splendor of his in country. Not so when he had learned how the oppression of the negroes bad extinguished in the white race almost every trait of character se which redeems and sanctifies human nature.

"God Almighty himself is doing it," he would say, when talking on this subject. "No man's hand can stay it. It is no other than the omnipotent God who has taken this mode of destroying slavery. We are but the instruments in his hands. We could not prevent it if we would. And let us strive as we might, the judicial blindness of the rebels would do the work of God without our aid, and in spite of all our endeavors against it."

AMEN!

Atlanta Monthly July, 1863. P143-145

GENERAL BUTLER IN NEW ORLEANS BEING A HISTORY OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE GULF IN THE YEAR 1862

BY JAMES PARTON

MASON BROTHERS, No. 7 MERCER STREET 1864

Also, General Butler in New Orleans, p145 & William Wells Brown, The Negro in the American Rebellion

Courtesy of www.RebelStore.com

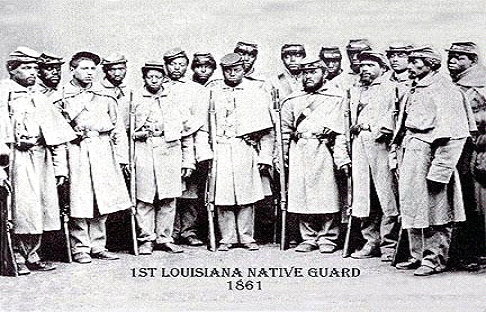

By the summer of 1862 Northerners were growing tired of being defeated by the South and fighting in the Civil War. The Union was running short of men. While stationed in New Orleans and short of men, Brigadier General Benjamin Butler turned to the free Black residents of New Orleans to help fight the war. New Orleans had a population of 150,000, of which 18,000 were slaves and 10,000 were free Blacks (James Parton, General Butler In New Orleans, P130). They were members of a Confederate regiment called “1st Louisiana Native Guard.” Free Blacks were enrolled by Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812 and again enrolled by Governor Moore in 1861(James Parton, General Butler In New Orleans, P134). They were the first Black regiment to be formed and they have the distinction of being the only Black regiment to be commanded by Black officers. Some were slave owners and some were mulattos. Would they switch sides and fight for the freedom of all Blacks? Butler had the following conversation with a group of them:

"But,"

I said, "I want you to answer me one question. My officiers, most of

them, believe that negroes won't fight."

"Oh,

but we will, "came from the whole of them.

"You

seem to be an intelligent man, "said I, to their spokesman;

"Answer me this question: I have found out that you know just as well

what this war is about as I do, and if the United States succeed in it,

it will put an end to slavery." They all looked assent.

"Then

tell me why some negroes have not in this war struck a good blow

somewhere for their freedom? "General, will you permit a question?"

"Yes."

"If we

colored men had risen to make war on our masters, would not it have been

our duty to ourselves, they being our enemies, to kill the enemy

wherever we could find them? and all the white men would have been our

enemies to be killed?"

"I

don't know but what you are right," said I. "I think that would be a

logical necessity of insurrection."

"If the

colored men had begun such a war as that, General, which general of the

United States army should we have called on to help us fight our

battles?" That was unanswerable.

"Well,"

I said, "why do you think that your men will fight?"

"General we come from a fighting race. Our fathers were brought here

slaves because they were captured in war, and in hand to hand fights,

too. We are willing to fight. Pardon me, General, but the only cowardly

blood we have got in our veins is the white blood."...

Better soldiers never shouldered a musket. They were intelligent,

obedient, highly appreciative of their position, and fully maintained

its dignity. They easily learned the school of soldier. I observed a,

very remarkable trait about them. They learned to handle arms and to

march more readily than the most intelligent white men. My drillmaster

could teach a regiment of negroes that much of the art of war sooner

than he could have taught the same number of students from Harvard or

Yale. ”…

Again, their ear for time as well as tune was exceedingly apt; and it

was wonderful with what accuracy and steadiness a company of negroes

would march after a few days' instruction…

Again, white men, in case of sudden danger, seek safety by going apart

each for himself. The negroes always cling together for mutual

protection. “

General Ben Butler, Butler's Book, Benjamin Butler, p492

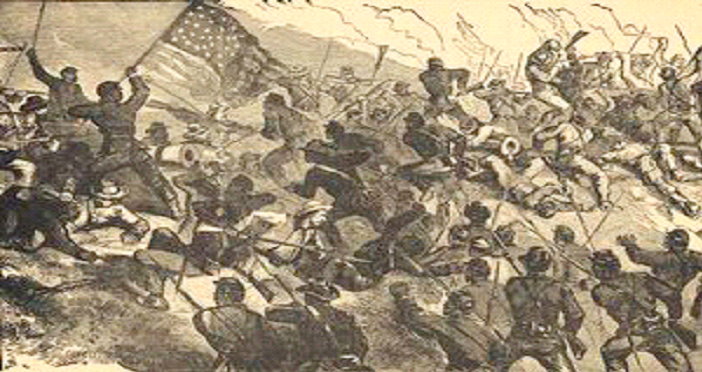

On May 27, 1863 the first large battle that included a Black regiment occurred at Port Hudson Louisiana. Butler had mustered them into Union service making them the first Black regiment to service the Union and the only Black regiment to have all Black officers. Butler’s First Regiment of Louisiana Native Guard lived up to their promise to Butler that they would fight with courage and honor. They attacked a heavily defended Confederate fort over five times until their force of 900 men was cut down to less than 300. The following article appeared in the New York Tribute.

" From " The New-York Tribune," June 8, 1863: -"Nobly done, First Regiment of Louisiana Native Guard! Though you failed to carry the rebel works against overwhelming numbers, you did not charge and fight and fall in vain. That heap of six hundred corpses, lying there dark and grim and silent before and within the rebel works, is a better proclamation of freedom than even President Lincoln's. A race ready to die thus was never yet retained in bondage, and never can be. Even the Wood copperheads, who will not fight themselves, and try to keep others out of the Union ranks, will not dare to mob negro regiments if this is their style of fighting. “

W. W. Brown, The Negro in the American Rebellion, p175

During the siege of Port Huston, a new school house was erected for the black soldiers who had been enlisted in that vicinity. When the school opened, the following speech was made by a colored soldier, called Sergt. Spencer. Spencer gave the following speech at the schools dedication.

" I has been a-thinkin' I was old man; for, on de plantation, I was put down wid de old hands, and I quinsicontly feeled myself dat I was a old man. But since I has come here to de Yankees, and been made a soldier for de Unite States, an' got dese beautiful clothes on. I feels like one young man ; and I doesn't call myself a old man nebber no more. An' I feels dis ebenin' dat, if de rebs came down here to dis old Fort Hudson, dat I could jus fight um as brave as any man what is in the Sebenth Regiment. Sometimes I has mighty feelins in dis ole heart of mine, when I considers how dese ere ossifers come all de way from de North to fight in de cause what we is fighten fur. How many ossifers has died, and how many white soldiers has died, in dis great and glorious war what we is in ! And now I feels dat, fore I would turn coward away from dese ossifers, I feels dat I could drink my own blood, and be pierced through wid five thousand bullets. I feels sometimes as doe I ought to tank Massa Linkern for dis blessin' what we has ; but again I comes to de solemn conclusion dat I ought to tank de Lord, Massa Linkern, and all dese ossifers. 'Fore I would be a slave 'gain, I would fight till de last drop of blood was gone. I has 'cluded to fight for my liberty, and for dis eddication what we is now to receive in dis beautiful new house what we has. Also I hasn't got any eddication nor no book-learnin', I has rose up dis blessed ebenin' to do my best afore dis congregation. Dat's all what I has to say now ; but, at some future occasion, T may say more dan I has to say now, and edify you all when I has more preparation. Dat's all what I has to say. Amen."

W. W. Brown, The Negro in the American Rebellion, p281

Copyright © 2006 The Gospel Army Black History Group. All rights reserved.

Revised: 12/08/09.